German Brewing between 1850 and 1900: Fermentation and Beer

|

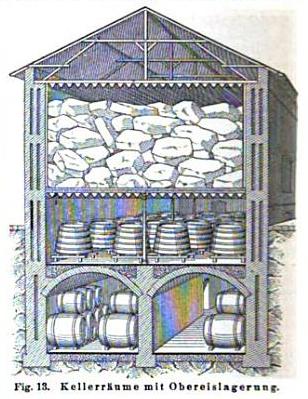

This second article about German Brewing in the later half of the 19th century covers the fermentation process and select beer styles as outlined in "Chemie fuer Laien" (1860). The first article (German Brewing between 1850 and 1900 : Malting and Wort Production) covered the brewing process from steeping the malt to cooling of the wort. Contents[hide]FermentationThe production of a good beer depends very much on the chemical process which we call fermentation. As a result the brewer has to give it his utmost attention. If it runs poorly the beer will be bad even if all other processes ran well and were controlled with care. But if it runs well it is possible to compensate for small mistakes made up to this point. Except if the wort got sour because in this case the 2nd fermentation already happened before the 1st one started. The beer fermentation is divided into two groups: top fermentation and bottom fermentation. Both types convert the sugar into alcohol and carbonic acid. But in beer this conversion should not be run until completion because one likes to get not only alcohol but also substance in the beer. The alcohol makes the beer invigorating, the carbonic acid gives it the refreshing taste, the unconverted sugars make it nutritious and the hops give it the spice. The fermentation should not destroy these properties nor should it affect them negatively and that's why it is so important to control it well. Today we know that there are fermentable and unfermentable carbohydrates in the wort and that the yeast can consume only the fermentable ones anyway Besides the mentioned primary purpose the fermentation should also facilitate the precipitation of a substantial amount of the protein. The more it is removed the more stable the beer will be. But the beer should never become void of any fermentation substrate, because unlike vine it is not a fully fermented beverage. If it would become that, it would stop being pleasantly drinkable. The carbon dioxide, which is formed through fermentation, is a substantial condition for the pleasant taste. In vine it is not present because there the fermentation is complete and all the carbon dioxide has escaped. It sounds as if the author was not aware that carbon dioxide can be trapped in the beer if the vessel is closed and that it can retain its carbonation even after complete fermentation. To prevent such staling of the beer it needs to retain enough fermentation substrate so it can slowly ferment throughout its existence. This is the same with Champagne. The temperature has a major effect on the course of the fermentation. At a temperature of 15 or more degrees (C) the fermentation is turbulent, quick and very active. At 7 C or less the fermentation is quiet and much slower. During the faster fermentation at higher temperatures the yeast rises to the top. This is brought on by carbon dioxide bubbles that lift the yeast to the top which is why this process is called top fermentation (Obergaerung). At lower temperatures less carbon dioxide is produced and the bubbles are too small to carry anything else but themselves and the yeast falls to the bottom. This is why this process is called bottom fermentation (Untergaerung). Top yeast causes top fermentation and bottom yeast causes bottom fermentation. But with the right temperature the type of the yeast can be changed. If one takes the foam rich of yeast of a top fermentation and adds it to wort and lets this stand at a temperature of 5C then the yeast is doing a bottom fermentation. Only little rises to the top. If one uses this yeast for fermenting fresh wort at low temperatures again then the former top yeast will completely transform into bottom yeast. Likewise can one create top fermentation and top yeast from bottom yeast by fermentation at 15 or more degrees C. This is an interesting observation. We know now that ale yeast is not going to change into lager yeast just based on the temperature but what may have happened is that the yeast that was used was not a pure ale or lager strain. It was a mix of strains and fermentation at lower temperatures benefited the lager type cells and fermentation at higher temperatures benefited the ale type cells. Light beers, which aren't expected to last a long time, are fermented with top yeast. It finishes the fermentation quickly, converts lots of the sugar into alcohol and produces lots of carbon dioxide (the reason for the strong foaming of the Weissbier). But because the fermentation is done at higher temperatures they tend to get sour very easily and the protein is not precipitated as completely. Such beers are not stable and need to be consumed quickly. For beers whose small amounts of sugar should not ferment completely, like the Bavarian and other lager beers, a the bottom fermentation is chosen. In this case the process is a slow one and the beers can be consumed months after being brewed. The protein settles out with the yeast and during their shelf life these beers will get better with every day. For top and bottom the process of fermentation is divided into three different phases. During the first, which starts after the addition of the yeast, sugar is converted into alcohol and new yeast is formed from the nitrogen compounds. The temperature of the fermenting substance rises. This part is called the rapid or wild fermentation. The second phase is the secondary fermentation (Nachgaerung). And while the conversion of the sugar still continues it is much slower and most of the yeast formed during the first phase settles out. The turbid beer clears up. The third phase is called the impalpable. It happens after the settling of the yeast and clarification. During that time the continued fermentation and yeast growth is so slow that there is still the fermentation of sugar and formation of carbon dioxide but the settling of the yeast is so slight that it is a mere haze on the side of the bottle on which it was laying. A haze that the maid pretends not being able to remove but which needs to be removed if one doesn't want to drink sour beer since it would immediately start the second stage of fermentation in the next beer that is filled into that bottle. Second fermentation means in this context the souring of the beer as this is seen as yet another fermentation stage that happens to the beer. The bottom fermentation Figure 1 - Schematic drawing of a fermentation building with ice storage on top, primary fermentation floor below and lagering cellars at the bottom. Meyers Konversationslexikon, 1893 Of significant importance is the locality in which the fermentation takes place. It has to be as deep as possible in the ground or surrounded by thick walls such that the outside temperature has no effect on the fermentation room. It needs to be vented but only at night as the temperatures during the day fluctuate too much and it is important to have a constant temperature. This is easiest during the winter. During fall and spring this is only possible through artificial means like sufficient ice reserves. The rooms have to be kept clean with the utmost care. Any foul smell is dangerous for the wort. It either influences the beer or lays the seed for spoilage. The vessels are usually made from wood and require an even greater cleanliness than the mash and cooling vessels as these only hold the wort for a few hours whereas the fermentation vats hold the beer for ten to fourteen days. These vats are oftentimes made quite large and can hold up to three thousand liter. In Bavaria they have ones that can hold even ten thousand liter for the beer production during the winter. But they can only be used during the winter as temperature rise during fermentation is significantly in such large volumes. Some brewers mix some of the wort from the cool ship with the yeast and then add this to the wort in the vat. Others take some wort, add it to the yeast and let this come to fermentation before they add it to the remaining wort. But every one swears that their method is the correct one and that large losses are eminent if it is done differently. It is clear that the complete distribution of the yeast in the wort is the first requirement and this distribution is best achieved if the yeast is first mixed with some wort until it is thin. This is then added to the main batch and stirred. This is repeated multiple times during the first 12 hours. The amount of yeast that should be pitched also depends on the view of the brewer. About 1/2 to 2/3 percent of the batch volume are taken. Too much yeast is disadvantageous because it can lead a displeasing taste to the beer, one that is similar to home baked bread. In addition to that, the longer the beer should last the less yeast should be used. The condition, that the yeas is in, and the fermentation temperature also need to be considered. During the first 12 hours the surface starts to get covered by a light white foam. These are small carbon dioxide bubbles which are covered with a thin layer of wort. This happens first close to the walls and then progresses towards the center. Most of the bubbles stay together but some burst and release their carbon dioxide which gives the peculiar stinging smell and that prickling in the nose. At first only when one leans into the vat, but later when more and more carbon dioxide is produced it will spill out of the vat and onto the floor and cover it such that a dog lost in the fermentation rooms immediately falls over and dies of asphyxiation. After three to four days the rising foam forms a foamy mass, the Kraeusen, which starts to subside as the fermentation slows. All that is left is a thin brown cover which mostly consists of the bitter resins of the hops. There is only little yeast in that layer. The yeast falls to the bottom which clears the beer more and more. The beer is now called Jungbier (young beer) or Gruenbier (green beer) and its clearing indicates that it is ready to be put into the lagering casks where it will continue with the much slower and longer secondary fermentation which is necessary to give the beer is drinkability. To test if a beer is ready to be racked to the lagering vessels a sample can be brought into a warm place. If it clears quickly and only little yeast settles out in flocks the beer is ready. This is the point in fermentation when the yeast starts to flocculate because all or most of the maltose has been consumed. The wort had a specific consistency. The sugar and dextrins made it heavier than water. But after the fermentation process it is much lighter. This dilution is called "Attenuation" in the new technical chemistry and it results from the fermentation having converted some of the heavier sugars into lighter alcohol. The weight of the wort is determined with an instrument called the Saccharometer (old wort for hydrometer). The depth with which it sinks into the wort indicates how much sugar and dextrins this wort has. Let's assume that the wort had a weight of 13 percent (This is pretty much equal to 13 Plato). After the eight to ten day main fermentation it shows only 6 percent. One would say that half of the sugar has been converted into alcohol. But this dilution can also be higher or lower. It depends very much on the way that the malt was kilned. Luftmalz (air malt) gives more sugar and thus more alcohol than heavily kilned brown malt which will not give an as "spirit rich" beer. It should be noted that it seems that they did not make a distinction between true and apparent extract of the beer. Since the 6 Plato were read from the beer with a hydrometer it means that this is the apparent extract and the real extract or sugar content is still higher than 6 percent. It is difficult to say how much time the main fermentation will take as much of this depends on the temperature and the quality of the yeast. But the stage to which it has progressed greatly influences the secondary fermentation. The more complete the primary fermentation was the slower the secondary fermentation will be. The brewer uses this fact to either produce a beer that can be consumed quickly but is less stable or a beer that takes longer to be drinkable but will be more shelf stable. When the beer is transferred the layer covering it needs to be removed. This is understood as it would give the beer a harsh bitter taste. The beer also needs to be clear and free of yeast. The last bit of beer that was standing over the yeast is allowed to settle and added later to the lagering casks. Fermentation produces new yeast which is a fungus that grows rapidly where there is food and the nitrogen rich compounds of the malt are especially suited. The old non-viable yeast settles first. The newly formed and most viable yeast settles next and after that a thin liquid yeast settles which is useless. It is interesting to note that Luis Pasteur discovered yeast in the same year that this book was published; 1860 Since the yeast is of such importance, brewers don't grow it new for each batch. They don't discard the sediment but remove the thin slurry on top and then scrape off the good yeast without getting too much of the old and useless bottom layer. This requires some skill and is done with large scrapers. Once the yeast as been collected and is stored in fresh water the vat is cleaned with water and large brooms using the utmost care to clean especially in the corners.  Figure 3 - Old wooden lagering casks. Visible in front of these casks is a Verschneidbock which was used to blend up to 3 casks. The sight glasses on that device were used to check when a particular cask is already drawing yeast. The upright tubes in the lower right corner are part of a Wasserspundapparat which is a pressure sensitive relieve valve where the counter pressure is created by columns of water. (Maisels Brewery Museum, Bayreuth, Germany) When the lager beer is transferred to the lagering casks they are generally filled completely and are closed (Verspunded) only once the secondary fermentation has ceased completely. The longer that secondary fermentation took the longer the beer needs to be kept bunged. Such beer also has the best stability and with longer storage it becomes stronger and better. It seems that at the time when this book was written the concept of the controlled venting of the head pressure in the casks was not commonly used yet. The amount of carbonation was only controlled though the amount of residual sugar at the time at which the cask was bunged. And based on the description this happened fairly late which leads me to believe that the lager beers of 1860 were not well carbonated at all. The Bavarian Brewing Museum however showed devices that were used to control the head pressure in the lagering vessels. Top FermentationWhen it comes to top fermented beers, the author lists a lot of different techniques. Interesting was that even some "Lagerbier" was top fermented, especially in northern Germany. The fermentation temperature was above 15C but the beer was filed into casks and lagered like the bottom fermented beer. This is basically how Alt and Koelsch are brewed. It also talks about summer beer and how it has to be top fermented because the low temperatures for bottom fermentation cannot be achieved during the summer. This contradicts the Figure 5 which shows select "Sommerbiers" as bottom fermented beers. These beers are generally consumed shortly after the primary fermentation is over and contain much more carbonation. They also have the tendency to go sour pretty quickly. The Bavarian wheat beer (Weissbier) for example is even brewed without hops Analysis data from select beers of the timeThe following tables have been taken from Brockhaus' Konversationslexikon, 1893. They list the alcohol by weight, real extract, starting extract (called "Stammwuerze" in German brewing) and real attenuation. In the translation I added the apparent attenuation for these beers as this is the attenuation number that we home brewers generally work with One thing that immediately becomes obvious is that most of these beers are very poorly attenuated by modern standards. Most beers have an apparent attenuation in the 60s and only a few make it into the 70s or higher. Back then beer was considered food and was expected to be nutritious. Another interesting observation is that the "summer beer (Sommerbier) was also a lager as it is listed under the bottom fermenting beers. Up to this point I always assumed the Sommerbiere were top fermented beers  Figure 4 - Analysis data of a few top fermented beers of the time. An apparent attenuation column has been added to the translation on the right hand side. From Brockhaus' Konversationslexikon, 1893  Figure 5 - Analysis data of a few bottom fermented beers of the time. An apparent attenuation column has been added to the translation on the right hand side. From Brockhaus' Konversationslexikon, 1893 Various Beer StylesThe following is a description of various beer styles as they were described in "Chemie fuer Laien". They obviously don't represent all the types of beers that were brewed back then. Salvator-BierAfter we looked at the brewing process we will have a look at especially famous and popular beers. We will start with the strongest of the bottom fermented beers, the Salvator-Bier. It gets its name from a brewery in Munich and its fame from its strength. Only the best ingredients are used and Bavarian breweries take pride in the fact that they brew their beer in an accredited traditional manner and with a constant quality. For the Salvator-Bier one takes 3 1/4 Berliner Scheffel (1 such Scheffel is 55 liter) malt and 3 1/2 Pfund (one such Pfund is 380g) to make 170 Quart beer (one such Quart is about 0.95 liter). The rest of the procedure is pretty much the standard Bavarian brewing method. The Salvator-Bier is always brewed using a decoction mash and the thick mash boils about 1/2 hour longer than usual. After the wort has been drawn into the boil kettle the length of the boil will determine the color of the beer. The hops are added 1 hour before the end of the boil. Assumed that the beer needs to boil for 5 hours to get the degree of color that the beer drinker prefers, the hops are added after the beer has already boiled for 4 hours, because only the finest part of the hops, the aroma and the essential oils, should be extracted. But that this wouldn't be better accomplished if the hops were only steeped is obvious. But this is how it is done in Bavaria and by doing so not only the finest but also the roughest part of the hops, the bitterness, is extracted. The wort is cooled to 10 C and pitched with more yeast than usual to accelerate the primary fermentation which still takes 12 days because of the strength of the wort. But it is not left in the primary fermentation vat until the beer has cleared. Instead it is transferred to the secondary fermentation casks for a strong secondary fermentation. Once it is complete the beer is transferred again for the actual lagering and maturation. During neither of these fermentations will the beer be spunded (bunged) which results in very low carbonation of the final beer and the taste is not as refreshing as one is used to from other Bavarian beers. In Berlin there is a brewery that brews a foaming Salvator-Bier which has this delicious and refreshing taste. The Munich Salvator-Bier has a deep dark color but is never as clear as wine. It is pretty clear but never what one would call bright. It also has a strong bitter finish which is evidence than not only the "finest" was extracted from the hops. The alcohol content is about 5 1/2 percent which makes it the one of the strongest beers brewed in Germany.

BockbierWith its 4 1/2 to 5 percent alcohol, it is the next strongest beer to the Salvator-Bier. And similar to the Salvator-Bier it is brewed with decoction mashing but with less malt and hops. Only 3 1/2 Berliner Scheffel malt and 2 1/2 Pfund hops are used to brew 200 Quart beer. But still this beer is much stronger, one might say double, as the common Bavarian beer. It is only served during the month of May. The Bavarians enjoy strong beer and would drink even more of that since the Hofbraeuhaus barely fits the guests which come there in May and has never enough wait staff. Which why it is not unheard of, that a guest may take the next empty mug, rinse it himself and get in line for the next beer. He even finishes it while standing and continues to do so as long as he dares if we wants to get home on his feet. Hardly anyone gets a seat during the Bockbier season. For the Bockbier The wort is chilled to 7 to 8 C and the fermentation takes 10 to 12 days. After that it is transferred to the lagering casks for a secondary fermentation. Once the strong secondary fermentation is complete the casks are topped off with Bockbier and lightly bunged. This allows some carbonation to build up but not enough for the beer to carry a big head. Only a slight layer of foam but more than what the Salvator shows. Bamberger BierThis belongs to those beers brewed in Bavaria for which the so called Lautermash is used. The crushed and dry malt is added to the mash tun and the water is brought to a boil in the boil kettle. Once it boils it is cooled to 85 C through the addition of cold water. This water is then added to the mash tun such that it enters from the bottom. The dry grain will swim on that water. The water is added in two to three steps and every half or third respectively is added after half an hour. Only after all the water has been added the mash is stirred. This takes about half and hour and after that the temperature of the mash will be about 10 C lower than what the water was in the kettle. The mash rests for about an hour after and then some wort is drawn off and moved to the boil kettle where it is boiled with all the hops. This basically "roasts" the hops and gives the Bamberger Bier its peculiar taste. Once the wort from the mash tun has cleared it is drawn into the boil kettle. One Scheffel malt and 2 1/2 to 3 Pfund of the best hops yields 7 Eimer beer (means buckets but I don't know how large such a bucket was). The cooling on the cool ship, pitching of the yeast and fermentation is the same as with the other bottom fermented beers. |